Client Inquiry:

I lead a team responsible for analyzing large-scale machine and equipment data to support product engineering. Most of our information is numerical, high-volume, and generated by connected equipment across the fleet. There is intense pressure inside the organization to use AI more aggressively, but almost all industry examples focus on text, search, or document workflows.

We experiment with natural language query tools, GenAI interfaces, and features like Databricks Genie, but the results are inconsistent. Queries often fail unless they are phrased like SQL, and non-experts struggle to validate whether outputs are correct. I am trying to understand how enterprises are actually applying generative AI to numerical data, where the real opportunities might be, and how to avoid approaches that create more maintenance, more risk, or more complexity than they remove.

Expert Takeaways:

1. Generative AI struggles with numerical data because it has no internal model of logic or causality

Language models work well with text because they predict the next word. They do not understand the rules that govern numerical data, the relationships between variables, or the constraints built into engineered systems. When asked to generate SQL or answer analytical questions, the model produces something that looks correct but has no guarantee of being correct.

This becomes visible as soon as queries require reasoning about relationships, granularity, or aggregation. The model can create valid SQL syntax, but the semantics can be wrong. It cannot distinguish between base-grain and summary-grain metrics, may repeat measures incorrectly after denormalizing, and cannot detect mixed-grain fact tables. Each of these errors can produce results that look plausible but are meaningfully incorrect.

For engineered systems that rely on precise interpretation of sensor data and machine behavior, this gap creates real risk. Without a way to validate correctness, GenAI becomes unreliable for direct analytical querying.

Key Insights:

- Language models do not understand cause and effect or logical dependence

- Syntactically correct SQL can still be semantically wrong

- Mixed grains, repeated measures, and aggregation traps confuse the model

- Accuracy is probabilistic, which makes correctness impossible to guarantee

- Reliability decreases sharply when users lack SQL experience

2. Natural language to SQL is feasible only for experts, because experts can recognize when the model is wrong

When a data scientist asks a question, the model performs reasonably well. Experts know how to phrase prompts, recognize when a join is incorrect, and validate outputs against intuition or experience. Non-experts cannot do this. They tend to accept or reject answers without knowing why, which makes natural language interfaces dangerous.

Even tools marketed for this use case struggle. Databricks Genie, for example, produces reasonable results for those with SQL intuition but fails quickly when asked questions by someone without data literacy. The gap is not in the UI. It is in the cognitive load placed on the user: they must know enough to detect a wrong answer before they can trust a right one.

This creates an uncomfortable tradeoff. If a data scientist must review every query, the efficiency gains disappear. If non-experts are expected to self-serve, the risk of misuse becomes unacceptable.

Key Insights:

- Experts can guide the model and validate correctness, but that limits scale

- Non-experts cannot reliably detect errors

- Review loops often negate efficiency gains

- Incorrect answers can appear highly plausible

- Natural language querying remains unreliable for middle-skill users

3. Opportunities grow when generative models support exploratory data analysis instead of trying to automate it

Trying to replace dashboarding or SQL with GenAI creates more problems than it solves. Supporting the analytical workflow is more promising. Analysts follow a sequence of exploration steps, and many of those steps can be anticipated. Language models can help generate the next likely action, propose EDA paths, or identify which tests or checks might be useful.

This shifts the model from a query engine to an augmentation tool. Instead of asking it to return correct results, the analyst asks it to help structure thinking. The model can outline steps, suggest variables to inspect, propose checks for missing values, or help prioritize data slices. The analyst stays in control, but the cognitive load decreases.

This approach improves speed without compromising correctness. It also fits more naturally into how analysts already work.

Key Insights:

- Generative models can aid thinking even if they cannot ensure correctness

- EDA workflows have predictable decision points that models can support

- The model can propose next steps, checks, or comparisons

- Analysts stay responsible for execution and validation

- This keeps the user in flow instead of forcing automation that breaks context

4. The real bottleneck in numerical domains is not analysis but data preparation and normalization

Machine and sensor data rarely come in a clean, unified structure. Sensors differ by vendor, units, calibration offsets, hardware generation, and collection frequency. Before meaningful analysis happens, teams must reconcile dozens of variations and normalize streams that appear similar but behave differently.

Generative AI does not fix this. In fact, it makes the problem more visible, because inconsistent preprocessing causes models to hallucinate relationships, misinterpret signatures, or misapply transformations. Real value emerges when teams invest in strong data modeling and reference data infrastructure.

Automation cannot replace the engineering rigor required to clean and standardize the data. However, once that foundation exists, augmentation tools become more reliable.

Key Insights:

- Vendor, unit, and calibration variations create large normalization burdens

- Reference data and rigorous modeling reduce EDA cycle times

- Clean sensor data increases the reliability of any AI support

- Generative tools fail quickly when fed inconsistent or mixed-grain data

- The biggest lift is improving the underlying data, not the model

5. Treat early AI experimentation as R&D rather than production and focus on what you learn instead of whether it works

Engineering cultures often treat failed prototypes as failures. AI requires the opposite mindset. Each experiment should be framed by what the team hopes to learn, not whether the model succeeds. This removes pressure, clarifies objectives, and helps leadership see the value of exploratory work.

The question shifts from “Did it work?” to “What does this result teach us about where GenAI can help and where it cannot?” This framing helps prevent blame when experiments fall short and directs the team toward more promising opportunities. It also aligns better with how mature AI teams operate.

Key Insights:

- Experiments should clarify where GenAI adds value and where it does not

- Learning goals should be explicit before work begins

- An R&D framing reduces blame and unrealistic expectations

- Failed experiments provide essential guidance for the next iteration

- Leadership responds better to learning narratives than to binary success metrics

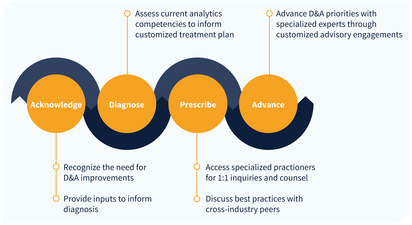

Expert Network

IIA provides guided access to our network of over 150 analytics thought leaders, practitioners, executives, data scientists, data engineers with curated, facilitated 1-on-1 interactions.

- Tailored support to address YOUR specific initiatives, projects and problems

- High-touch onboarding to curate 1-on-1 access to most relevant experts

- On-demand inquiry support

- Plan validation and ongoing guidance to advance analytics priority outcomes

- Monthly roundtables facilitated by IIA experts on the latest analytics trends and developments